Examining Market Volatility Around Economic Data Releases and Recessions

Introduction

Market volatility dynamics have persistently perplexed investors over the course of the current economic cycle. Disruptions stemming from the Global Covid Pandemic, followed by the first serious bout of inflation that the US economy has experienced in 40 years, and the subsequent remarkably vibrant but uneven economic recovery, have all conspired to repeatedly defy markets consensus. Against this backdrop, the attention being paid to macro-economic variables has surged, but the thinking surrounding the impact of these factors on volatility markets is muddled. This paper seeks to systematically examine the behavior of volatility in response to key economic data releases, as well as to investigate how that behavior changes heading into recession. Our analysis has two main takeaways. The first key conclusion is that economic releases tend to reduce, rather than increase, implied volatility. The second is that volatility only sees a modest increase as the economy enters into a recession. We note that volatility measures only really pick up later in the economic adjustment process, well after the economic contraction begins.

Gauging Market Volatility

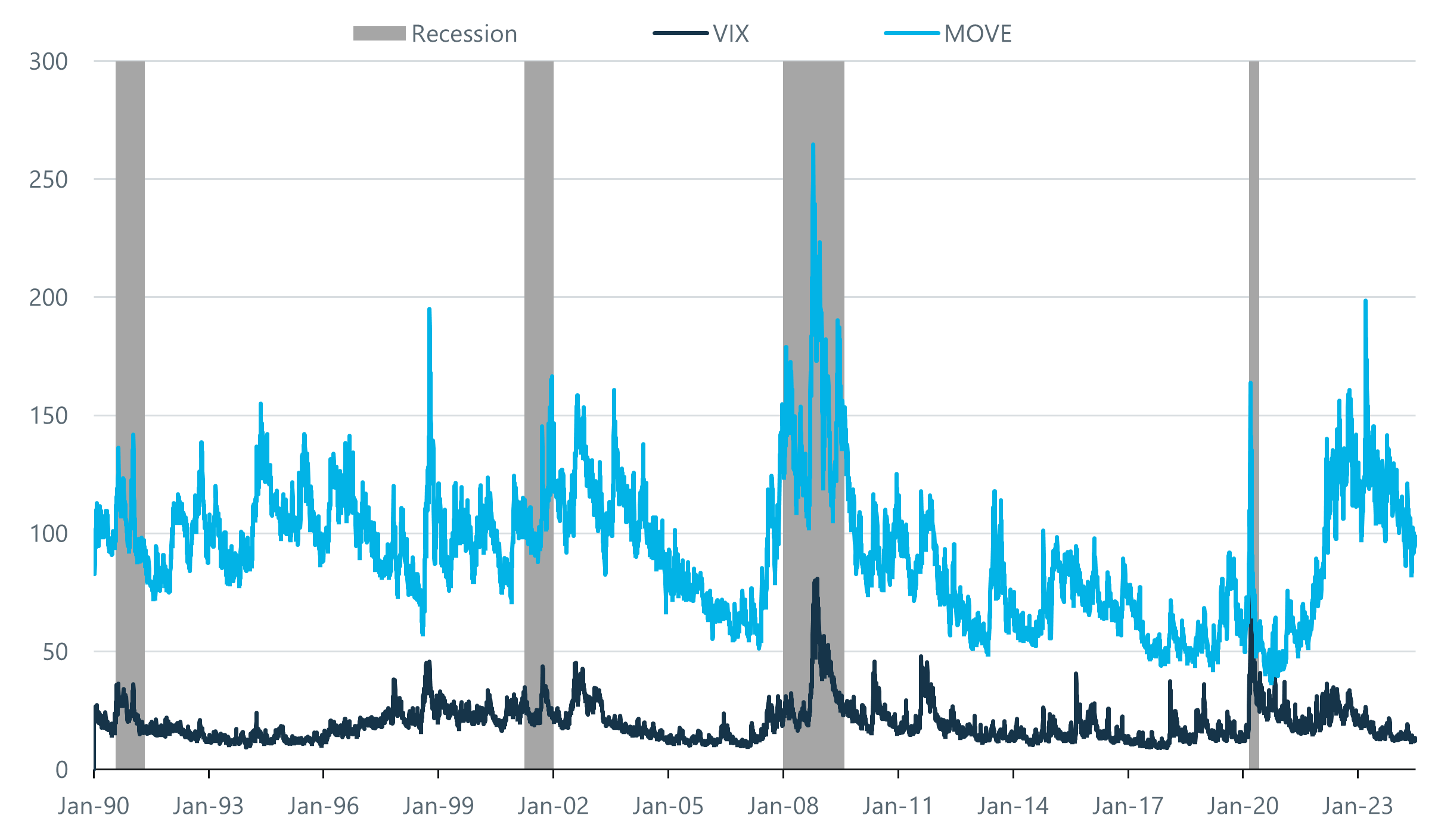

There are many ways to measure volatility, but for the purposes of this paper, we focus on two key metrics when discussing market volatility for equities and rates: the VIX index and the MOVE index, respectively. Using these measures as proxies has several advantages, most importantly their widespread familiarity and their long histories. Studying market variables over economic cycles requires data that goes back more than one cycle of expansion and contraction. Both the VIX and the MOVE indices have data going back to (at least) January 1990, the point at which our analysis starts.

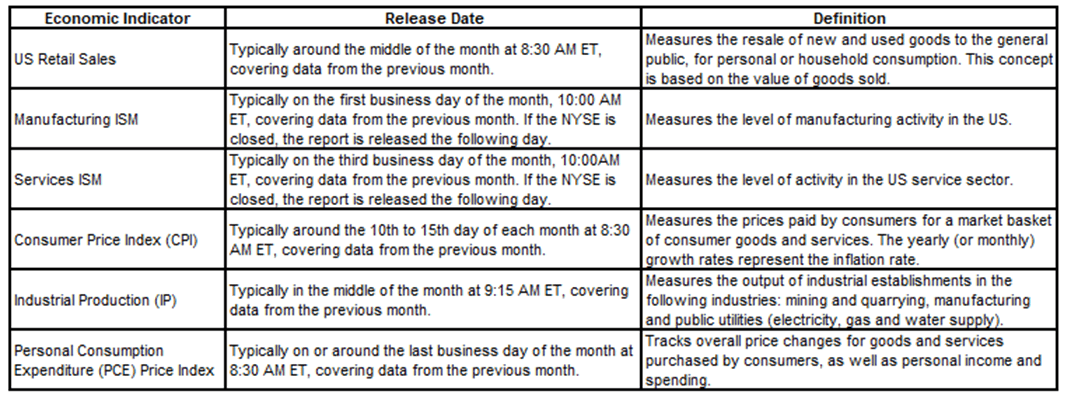

To measure the impact of discrete economic data announcements, this paper focuses on seven key macro-economic reports. Parsing through the types of economic data releases, we focus on those with history going back to the start of 1990, are closely followed by market participants, and have release dates that must be known in advance. Based on this selection criteria, our analysis uses the following releases: Retail Sales, Manufacturing ISM, Services ISM, Non-Farm Payrolls (NFP), Consumer Price Index (CPI), Industrial Production (IP), and Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Economic Data Indicators, Release Dates, and Sources

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

We also examine the period leading into a recession and the period shortly after the start of the recession. The dates used for the start of a recession are the official designations published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). For this analysis, we looked at the three months prior to the start of a given recession and following six months. Going back to January 1990, our sample period includes four recessions, but this study excludes the Covid contraction because it was a purely exogenous shock induced by the pandemic. This paper is more interested in endogenously-generated economic recessions, since they are far more typical and to some degree more predictable. The data period ends in June 2024, therefore covering a total of 34.5 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Volatility and Recessions

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

Setting the Volatility Record Straight

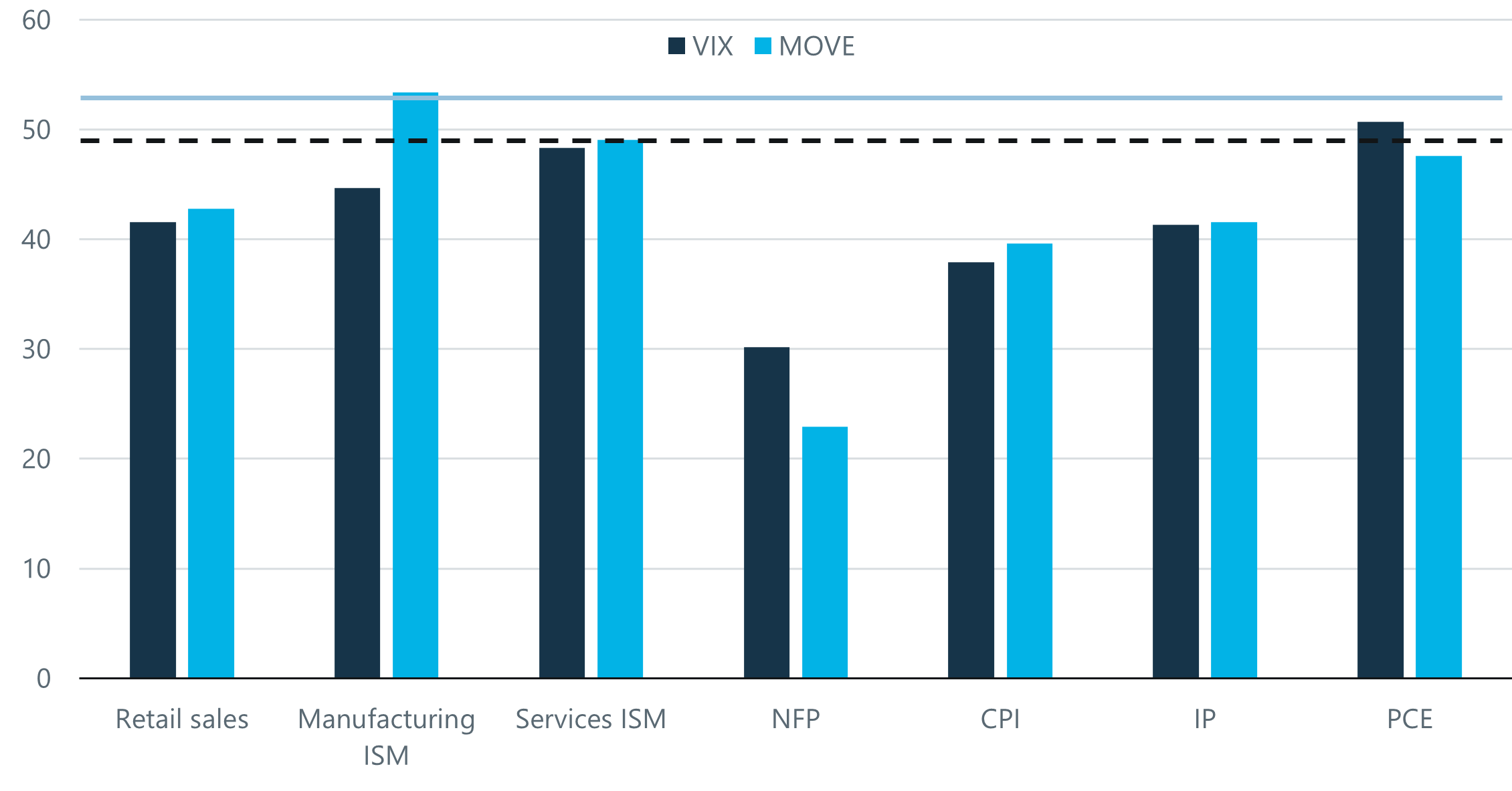

Economic data is generally volatility-suppressing. Market participants often warn of the possibility that some forthcoming piece of economic data may surprise markets and therefore catalyze a surge higher in volatility metrics. But over time, we find that this is a losing bet. Both the VIX and MOVE indices consistently see more declines than increases on days when key economic data is released (Figure 3).

This is the case for most releases – not just as a straight tabulation of up days versus down days, but even in comparison to the average trading day. Volatility behavior is not normally distributed, meaning volatility indices typically see more down days than up days. Over our sample period, the VIX and MOVE indices ended the day higher roughly 45% of the time (dashed line in Figure 3). With the exceptions of both the Manufacturing and Services ISMs as well as PCE, the volatility indices see more frequent declines on days when the data is released relative to the moves on a typical day.

Figure 3: Percentage of Volatility-Up Days on Data Release Days

Source: Capstone and Bloomberg

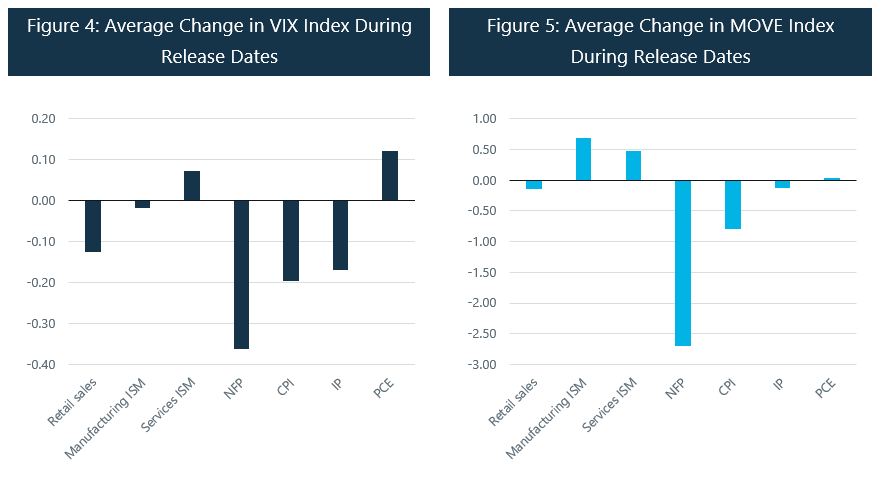

A reasonable counterargument to this line of thinking is that simply looking at up-versus-down days is too simplistic, since magnitudes matter. Theoretically, fewer but more significant up days could still make it worthwhile to be long volatility heading into big data releases. It turns out however that this is not the case either. Even in magnitude-adjusted terms, we found that most economic data releases are still volatility-suppressing the majority of the time. This is true for both the VIX and the MOVE indices (Figures 4 & 5). The only meaningful exceptions are the Services ISM and PCE for equity volatility, and both the Manufacturing and Services ISMs for rates volatility.

Source: Capstone and Bloomberg

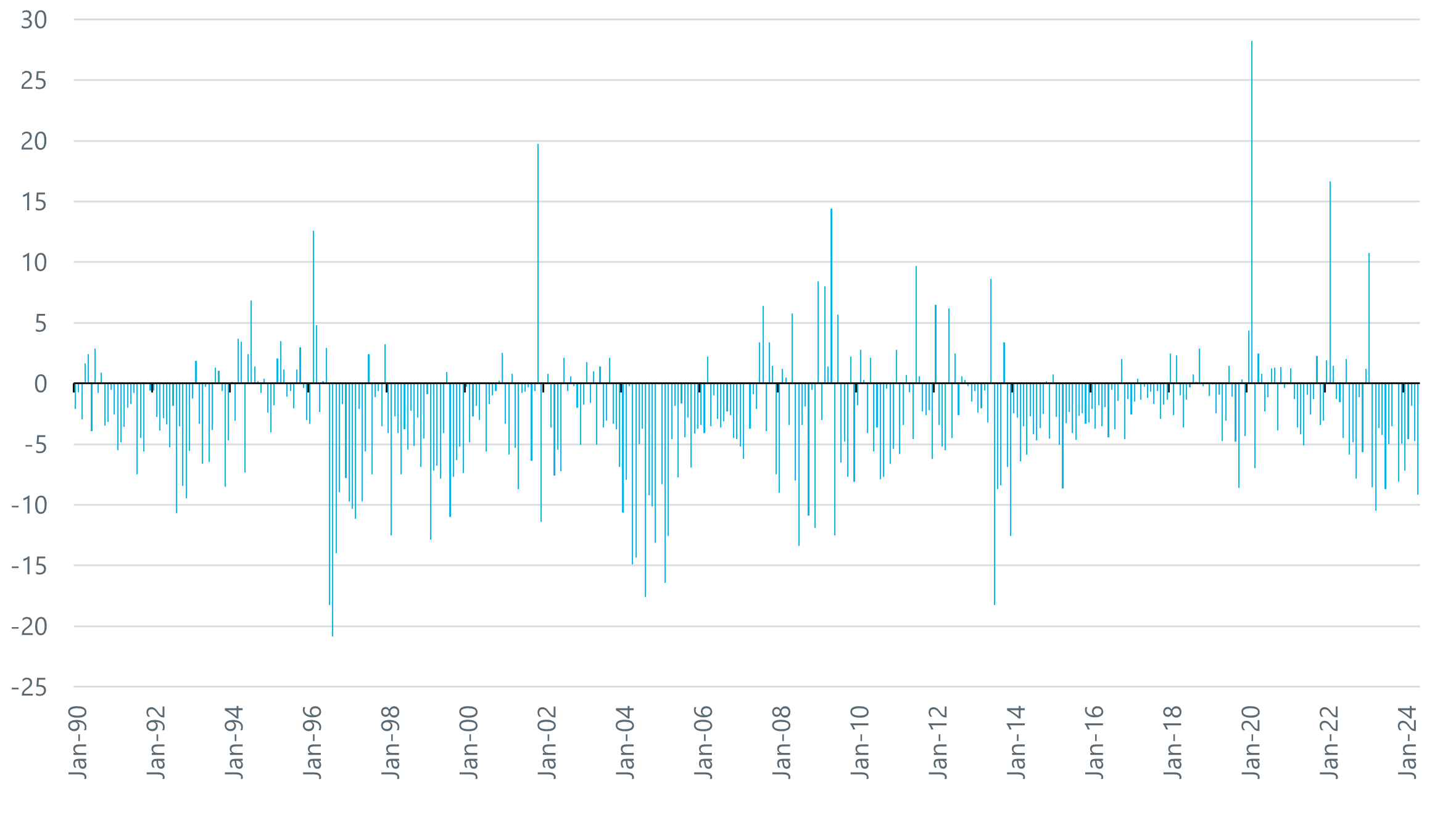

The second major takeaway here is that the NFP release is particularly volatility-suppressing. As evidenced in Figure 2 above, VIX and MOVE indices respectively closed lower 70% and 77% of the time on NFP days. Similarly, the declines in both equities and rates volatility in response to NFP releases were far more significant than the impact from any other economic data, in either direction (as evidenced in Figures 4 & 5). This is especially true on the rates side, in both mean and modal terms. There are not many reliable rules-of-thumb in markets, but selling rates volatility heading into an NFP release seems to come pretty close (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Change in MOVE Index on day of NFP Release

Source: Capstone and Bloomberg

Why might this be the case? Quite simply, markets price in a risk premium ahead of a given NFP announcement out of fear of a possible surprise. If that fear does not materialize, that risk premium gets priced out and volatility drops. Clearly, as seen by the results, more often than not, it does not. This is particularly remarkable because NFP data is notoriously hard to predict, and therefore is a constant source of surprise to investors. This has remained the case even since the onset of the Covid pandemic, when NFP surprises have persistently been larger (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Magnitude of Surprise to NFP (Median Estimate – Realized, in thousands)

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

Why the ISMs and PCE are partial exceptions to the broader trend is a more complicated question, and a topic that requires a separate deeper dive. One possible hypothesis is that ISM releases are the most timely and forward-looking major economic releases that the market gets. As a result, they carry more new information for investors than the other releases, and perhaps therefore have greater capacity to influence the macro narrative. Though PCE is less timely, it is comprehensive and may therefore also be more impactful in this sense. In any case, more investigation is required here.

Volatility in the Time of Recession

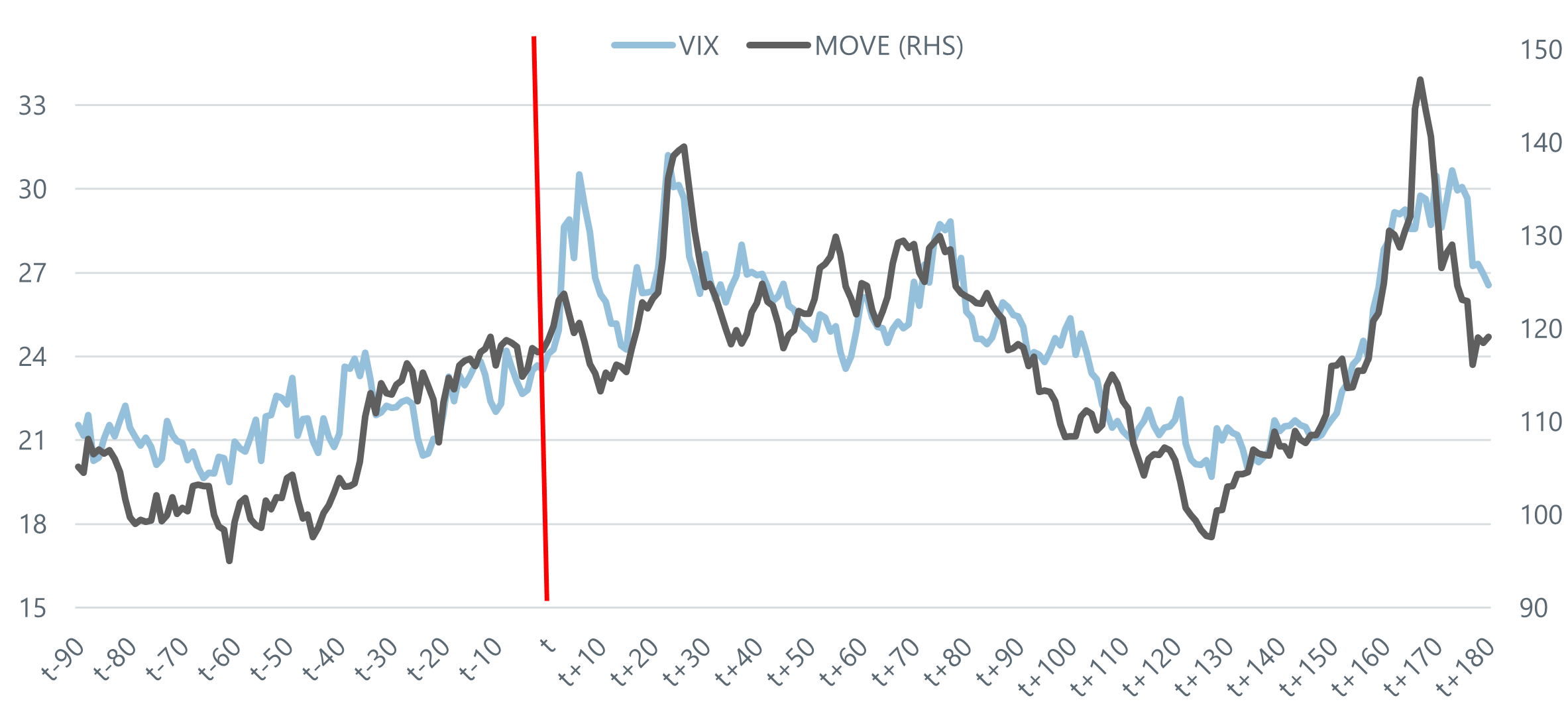

Not all stages of the economic cycle have the same characteristics, and not all volatility spikes are created equal. Another piece of conventional wisdom is that volatility picks up as economic data deteriorates heading into a recession. This is only partially true, and to a lesser degree than is commonly believed. Looking across the last three endogenously driven recessions (1990, 2001, and 2007-2009), volatility measures did increase after the economy entered recession, but the increase was modest. What is more notable, implied volatility saw an initial peak shortly after the official start of a recession, and then steadily declined. Here too, the pattern holds across both equities and rates (Figure 8).

Figure 8: VIX and MOVE indices entering into recession (t = 0 at start of recession)

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

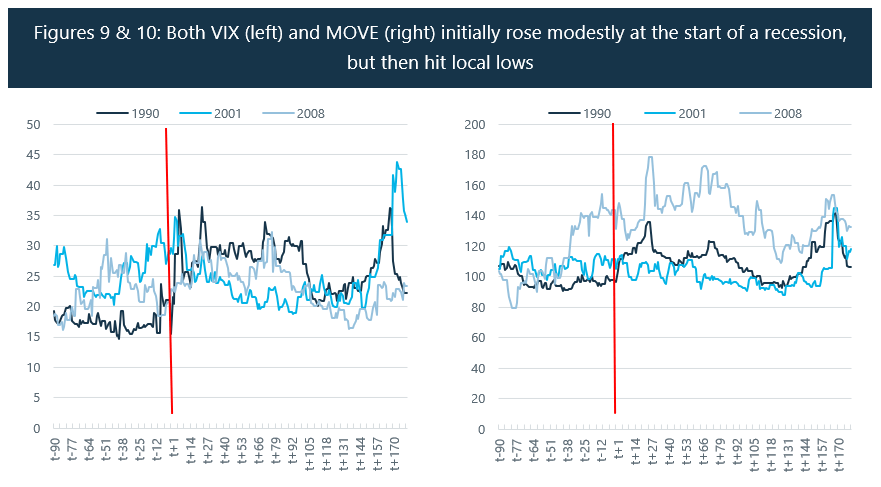

Interestingly, this is a generalizable finding across different cycles; the same basic pattern holds across all three recessions. In all three cases, the VIX and MOVE indices were making new lows about 90 calendar days after the start of recession, both dropping below where they were in the month leading up to said recession (Figure 9 & 10). This was then followed by a period of resurgent volatility in the subsequent 90 days after the start of a recession, though the magnitude of that surge varied considerably. Why this is the case may be due to idiosyncratic factors unique to each recession, but the main takeaway here is that investors do not need to try and time the start of recession to be long volatility. That opportunity often comes later once the recession has already begun.

Figures 9 & 10: Both VIX (left) and MOVE (right) initially rose modestly at the start of a recession, but then hit local lows

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

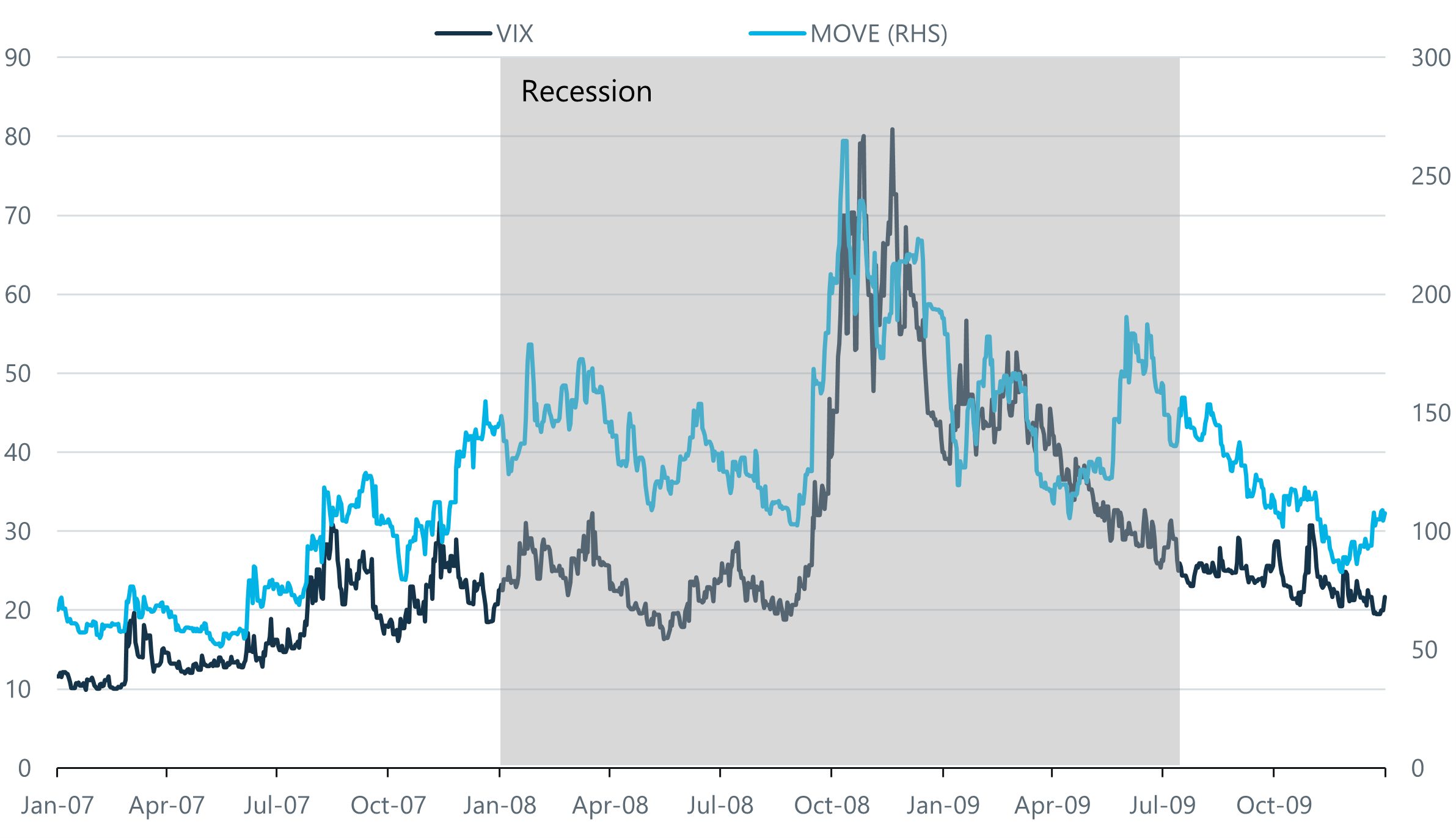

Extending this point further, it is worth highlighting that the particularly large volatility spike during the Global Financial Crisis happened well after the recession had started (Figure 11). This is the surge in volatility that investors often associate with a significant economic contraction and remember years later. Yet that panic point did not occur until October 2008, 10 months after the recession had begun (and past the 6-month time horizon this study looked at, as our goal is to focus on the particular volatility dynamics during the period surrounding the start of recessions).

Figure 11: The surge in volatility during GFC, 10 months after the recession had started

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg.

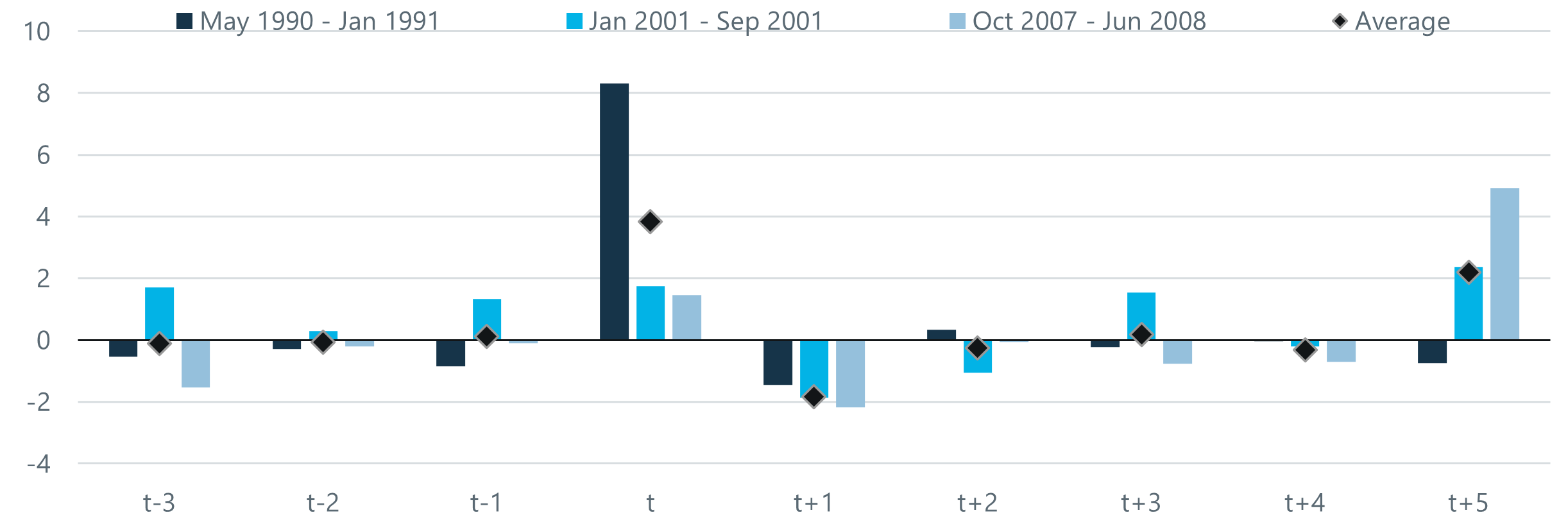

Looking at the volatility response to different economic releases heading into recession also offers some useful lessons. Once again, the NFP release stands out here, but in a different way. Unlike normal markets where NFP is equity volatility-suppressing, it is a clear source of higher volatility heading into recession. In all three recessions in our sample, NFP drove the VIX higher the first month of each recession (Figure 12). In each case, a poor NFP print led investors to downgrade their growth views and price in greater downside tail risks. Notably, the following NFP release led to a drop in VIX in each case.

Figure 12: Change in VIX on NFP days heading into recession (t = 0 first month of recession)

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

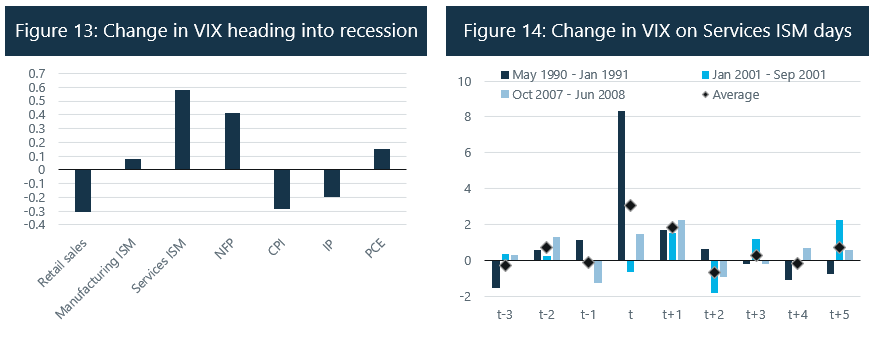

The ISMs and PCE stand out here too as being the only other releases that have been associated with a net higher VIX during downward turns in the cycle (Figure 13). The impacts of the manufacturing ISM and PCE however are modest and uneven. Only the Services ISM really qualifies as a strong signal (Figure 14). The Services ISM has driven VIX higher consistently at the start of recessions, which makes intuitive sense since its release represents the newest information about the largest share of the US economy.

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

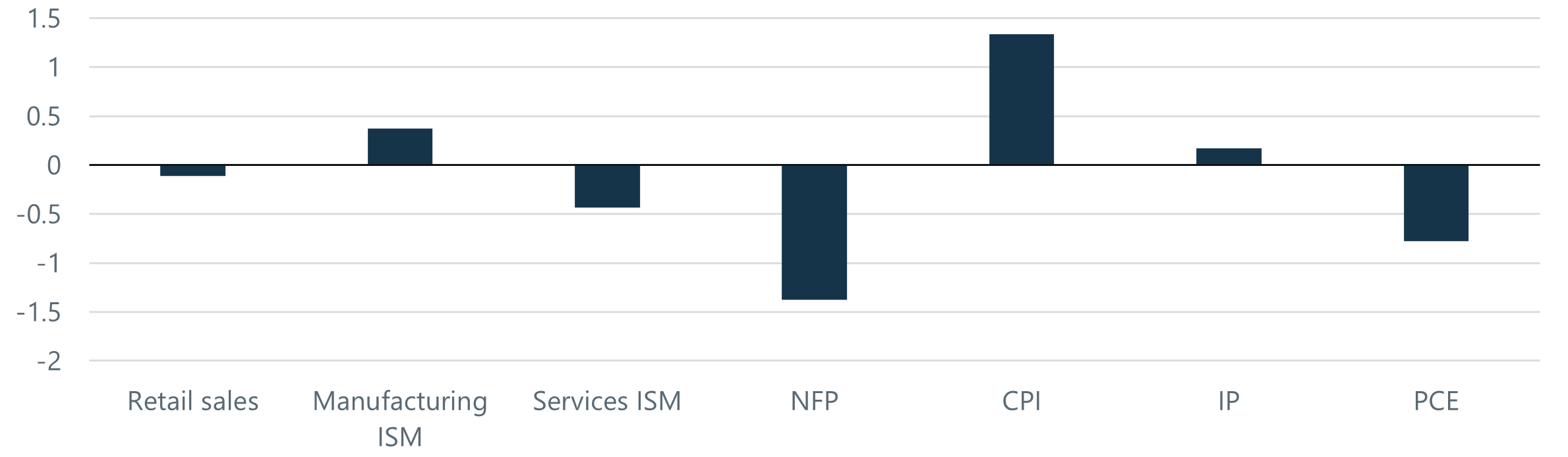

Interestingly, the takeaways are completely different on the rates side. The only meaningful positive contributor to the MOVE index during these periods is the CPI release (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Change in MOVE heading into recession

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

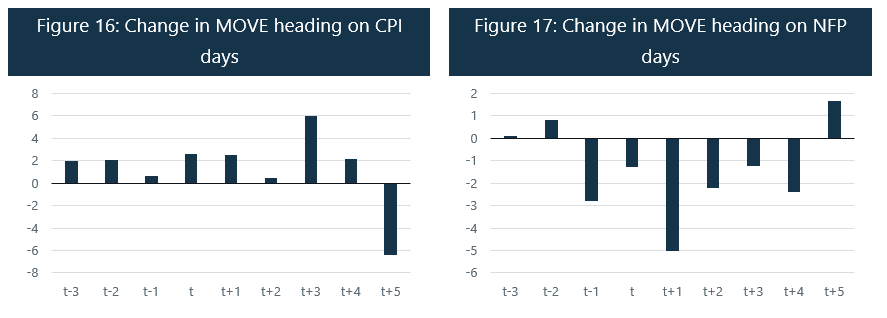

On net, CPI has driven rates volatility higher heading into and shortly after the start of recession with remarkable consistency (Figure 16). Conversely, NFP was true to form in being a persistent volatility-suppressor (Figure 17). We believe there is an intuitive explanation for this: all else equal, the rates market is more sensitive to inflation dynamics than it is to growth dynamics, whereas the opposite holds true for the equity market.

Source: Capstone, Bloomberg

Conclusion

Having a sample size of just three recessions has obvious drawbacks and limits the generalizability of any conclusions. Nevertheless, this paper highlights two key findings, namely (1) economic releases tend to reduce, rather than increase implied volatility, and (2) volatility only sees a modest increase as the economy is entering recession, only really rising later in the economic adjustment process. It also challenges conventional wisdom on the interaction between volatility and macro-economic data, outlining the logic behind these results. Lastly, we identify areas for further study, including a more rigorous quantitative assessment of the relationship between some of the key macroeconomic indicators and volatility metrics, an extension of this analysis to examine the behavior of different tenors across the term structure, and an expansion of this analysis to other asset classes.

Disclaimers

The content of this document is confidential and proprietary and may not be reproduced or distributed, in whole or in part, without the express written permission of Capstone Investment Advisors, LLC (“Capstone”). The content herein is based upon information we deem reliable but there is no guarantee as to its reliability, which may alter some or all of the conclusions contained herein. No representation or warranty is made concerning the accuracy of any data compiled herein. In addition, there can be no guarantee that any projection, forecast or opinion in these materials will be realized. These materials are provided for informational purposes only, and under no circumstances may any information contained herein be construed as investment advice. This document is not an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, product or services sponsored or provided by Capstone. This document is not an advertisement and is not intended for public use or additional further distribution. By accepting receipt of this document the recipient will be deemed to represent that they possess, either individually or through their advisors, sufficient investment expertise to understand the risks involved in any purchase or sale of any financial instruments discussed herein. Neither this document nor any of its contents may be used for any purpose without the consent of Capstone.

The market commentary contained herein represents the subjective views of certain Capstone personnel and does not necessarily reflect the collective view of Capstone, or the investment strategy of any particular Capstone fund or account. Such views may be subject to change without notice. You should not rely on the information discussed herein in making any investment decision. Not investment research. The market data highlighted or discussed in this document has been selected to illustrate Capstone’s investment approach and/or market outlook and is not intended to represent fund performance or be an indicator for how funds have performed or may perform in the future. Each illustration discussed in this document has been selected solely for this purpose and has not been selected on the basis of performance or any performance-related criteria. This document is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy securities. Capstone is not recommending any trade and cannot since it is not a broker-dealer. Nothing in this document shall constitute a recommendation or endorsement to buy or sell any security or other financial instrument referenced in this document.

Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice.

Investments in alternative investments are speculative and involve a high degree of risk. Alternative investments may exhibit high volatility, and investors may lose all or substantially all of their investment. Investments in illiquid assets and foreign markets and the use of short sales, options, leverage, futures, swaps, and other derivative instruments may create special risks and substantially increase the impact and likelihood of adverse price movements.

Reference to Instruments and Indices:

References to indices are included for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to apply that any Capstone fund or account is similar to such index in composition or element of risk.

CBOE Volatility Index (VIX Index): The CBOE Volatility Index® (VIX® Index) is based on real-time prices of options on the S&P 500 Index (SPX) and is designed to reflect investors’ consensus view of future (30-day) expected stock market volatility.

S&P 500 Index: The S&P 500 Index consists of 500 stocks chosen for market size, liquidity, and industry group representation. It is a market-value weighted index (stock price times number of shares outstanding), with each stock’s weight in the Index proportionate to its market value.

MOVE Index: The MOVE Index measures U.S. bond market volatility by tracking a basket of OTC options on U.S. interest rate swaps. The Index tracks implied normal yield volatility of a yield curve weighted basket of at-the-money one month options on the 2-year, 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year constant maturity interest rate swaps.

THESE SECURITIES SHALL NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD IN ANY JURISDICTION IN WHICH SUCH OFFER, SOLICITATION OR SALE WOULD BE UNLAWFUL UNTIL THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE LAWS OF SUCH JURISDICTION HAVE BEEN SATISFIED.

Notice to Investors in California

This information is confidential. If you are not the intended recipient, please delete it without further distribution and reply to the sender that you have received the message in error. This message is provided for information purposes and should not be construed as a solicitation or offer to buy or sell any securities or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction. California residents should review Capstone’s California Privacy Notice: http://www.capstoneco.com/content/uploads/2019/12/CCPA-fund-Manager-Website-Notice.pdf.

Notices to Investors Outside of the U.S.

Capstone is not registered, authorized or eligible for an exemption from registration in all jurisdictions. Therefore, services described in these materials may not be available in certain jurisdictions. These materials do not constitute an offer or solicitation where such actions are not authorized or lawful, and in some cases may only be provided at the initiative of the prospective investor. Further limitations on the availability of products or services described may be imposed. These materials are only intended for investors that meet qualifications as institutional investors as defined in the applicable jurisdiction where materials are received.

Notice to Investors in Australia

Capstone is regulated by the SEC under US laws, which differ from Australian laws. This material provided to you is factual in nature. It is not an offer or advice, and is not intended to recommend or state an opinion of Capstone. This document in its entirety is prepared by Capstone Investment Advisors, LLC (“Capstone”), a corporate authorized representative (number 1279754) of SILC Fiduciary Solutions Pty Ltd ACN 638 984 602 (AFSL 522145). The authority of Capstone is limited to providing general financial product advice to wholesale clients. Investors should seek independent financial advice before making any investment decisions.

Before acting on any advice or information in this document you should consider, with or without the assistance of suitable expert advice, whether it is appropriate for your circumstances. To the maximum extent permitted by law, SILC, Capstone and their directors and officers disclaim all liability or responsibility whatsoever for any direct or indirect loss or damage of any kind which may be suffered by any person through relying on anything contained or omitted from this document, caused by viruses or faults contained in this document or otherwise arising out of the use of any part of the information contained in this document.

Notice to Investors in Canada

The content of these materials has not been reviewed by any Canadian Securities Regulatory Authority and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy securities in any jurisdiction where such offer or solicitation would be unlawful, and such content does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or an advertisement in respect of securities in any province or territory of Canada.

Notice to Investors in China

These materials, which have not been submitted to the Chinese Securities and Regulatory Commission, may not be supplied to the public in China or used in connection with any offer for the subscription or sale of interests in any investment product to the public in China.

Notice to Investors in the European Union and United Kingdom

These materials are only intended for investors that meet qualifications as institutional investors as defined in the applicable jurisdiction where materials are received, which includes only Professional Investors as defined by the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID). These materials are not for use by retail clients and may not be reproduced or distributed without Capstone’s permission.

Notice to Investors in Hong Kong

Warning: The contents of this document have not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in Hong Kong. You are advised to exercise caution in relation to the document. If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this document, you should obtain independent professional advice.

Notice to Investors in Japan

No filings have been made with respect to any of Capstone’s funds in Japan and the strategy is currently not intended for investment by Japanese investors. Thus, we are not providing this material to you for purposes of soliciting an investment in fund securities by you or your client investors, but rather to illustrate the manner in which we would plan to manage an asset management mandate (structured in a mutually acceptable and compliant form) granted to us by you should you so elect. By accepting this material, you acknowledge, confirm and agree that you have never been contacted by a representative of the fund or its manager in any manner which may amount to an offer to buy (or solicitation of an offer to buy) any interests in the fund in Japan.

Interests in the fund are a security set forth in Article 2, Paragraph 2, Item 6 of the Financial Instruments and Exchange Law of Japan (the “FIEA”). No public offering of interests in the fund is being made to investors resident in Japan and in accordance with Article 2, paragraph 3, Item 3, of the FIEA, no securities registration statement pursuant to Article 4, paragraph 1, of the FIEA has been made or will be made in respect to the offering of interests in the fund in Japan. The offering of interests in the fund in and investment management for the fund in Japan is made as “Special Exempted Business for Qualified Institutional Investors, Etc.” under Article 63, Paragraph 1, of the FIEA. Thus, interests in the fund are being offered only to certain investors in Japan. Neither the Fund nor any of its affiliates is or will be registered as a “financial instruments firm” pursuant to the FIEA. Neither the Financial Services Agency of Japan nor the Kanto Local Finance Bureau has passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of the Fund’s Offering Documents or otherwise approved or authorized the offering of interests in the fund to investors resident in Japan.

As of April 2024, Capstone Fund Services, LLC (“CFS”) and Capstone Fund Services II, LLC (“CFS II”) each have submitted Notification Form for Specially Permitted Businesses for Qualified Institutional Investors, etc. to the Kanto Local Finance Bureau in accordance with the FIEA. Each CFS and CFS II are organized for the purpose of engaging in any and all activities permitted under applicable law, including providing, directly or indirectly through Affiliates or joint ventures, a full range of investment advisory and management services. In connection with the foregoing, each of CFS and CFS II may serve as general partner or managing member (or in a similar capacity) with respect to other vehicles in the future, as determined by their Managing Member. Neither of the aforementioned funds nor any of its affiliates is or will be registered as a “Financial Instruments Business Operator” pursuant to the FIEA.

Notice to Investors in Korea

Capstone is not making any representation with respect to the eligibility of any recipients of this material to acquire any products managed by Capstone under the laws of Korea, including but without limitation the Foreign Exchange Transaction Act and Regulations thereunder. Capstone has not registered any shares with regards to any of its products under the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act of Korea, and none of the shares may be offered, sold or delivered, or offered or sold to any person for re-offering or resale, directly or indirectly, in Korea or to any resident of Korea except pursuant to applicable laws and regulations of Korea.

Notice to Investors in Kuwait

This material has not been approved for distribution in the State of Kuwait by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry or the Central Bank of Kuwait or any other relevant Kuwaiti government agency. The distribution of this material is, therefore, restricted in accordance with law no. 31 of 1990 and law no. 7 of 2010, as amended. No private or public offering of securities is being made in the State of Kuwait, and no agreement relating to the sale of any securities will be concluded in the State of Kuwait. No marketing, solicitation or inducement activities are being used to offer or market securities in the State of Kuwait.

Notice to Investors in Russia

The securities (financial instruments) are not intended for placement in (or on the territory of) the Russian Federation and are not advertised or otherwise publicly marketed and/or offered for sale to the public in the Russian Federation. This confidential private placement memorandum is not subject to registration pursuant to Section 51.1 of the Russian Federal Law No. 39-FZ of April 22, 1996 (as amended) “on the Securities Market”.

Notice to Investors in Saudi Arabia

Capstone is not registered in any way by the Capital Market Authority or any other governmental authority in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This presentation does not constitute and may not be used for the purpose of an offer or invitation

Notice to Investors in Singapore

This material has not been submitted to the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Accordingly, this material and any other document or material in connection with the offer or sale, or invitation for subscription or purchase, of shares may not be circulated or distributed, whether directly or indirectly, to persons in Singapore other than (i) to an institutional investor pursuant to Section 304 of the Securities and Futures Act, Chapter 289 of Singapore (the “SFA”)) or (ii) otherwise pursuant to, and in accordance with the conditions of, any other applicable provision of the SFA.

Notice to Investors in Switzerland

The offer and the marketing of the fund’s Shares in Switzerland will be exclusively made to, and directed at, qualified investors (the “Qualified Investors”), as defined in Article 10(3) and (3ter) of the Swiss Collective Investment Schemes Act (“CISA”) and its implementing ordinance, at the exclusion of qualified investors with an opting-out pursuant to Art. 5(1) of the Swiss Federal Law on Financial Services (“FinSA”) and without any portfolio management or advisory relationship with a financial intermediary pursuant to Article 10(3ter) CISA (“Excluded Qualified Investors”). Accordingly, the fund has not been and will not be registered with the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (“FINMA”) and no representative or paying agent have been or will be appointed in Switzerland. This marketing materials, the Memorandum and/or any other offering or marketing materials relating to the fund’s Shares may be made available in Switzerland solely to Qualified Investors, at the exclusion of Excluded Qualified Investors. The legal documents of the fund may be obtained free of charge from [email protected].

Notice to Investors in the UAE

Capstone has not received authorization or licensing from the Central Bank of the UAE, the SCA or any other authority in the UAE to market or sell interests within the UAE. Nothing contained in this presentation is intended to constitute UAE investment, legal, tax, accounting or other professional advice. This presentation is for the informational purposes only and nothing in this presentation is intended to endorse or recommend a particular course of action. Prospective investors should consult with an appropriate professional for specific advice rendered on the basis of their situation.